Submitted by Anne Landman on

Many of the of the tobacco industry's underhanded strategies and tactics have been exposed, thanks to landmark legal cases and the hard work of public health advocates. But we are still uncovering the shocking lengths to which the industry has gone to protect itself from public health measures like smoking bans. Now we can thank the city of Pueblo, Colorado, for an opportunity to look a little bit deeper into how the industry managed the deadly deceptions around secondhand smoke.

Many of the of the tobacco industry's underhanded strategies and tactics have been exposed, thanks to landmark legal cases and the hard work of public health advocates. But we are still uncovering the shocking lengths to which the industry has gone to protect itself from public health measures like smoking bans. Now we can thank the city of Pueblo, Colorado, for an opportunity to look a little bit deeper into how the industry managed the deadly deceptions around secondhand smoke.

A new study, now the ninth of its type and the most comprehensive one yet, has shown a major reduction in hospital admissions for heart attacks after a smoke-free law was put into effect.

On July 1, 2003, the relatively isolated city of Pueblo, Colorado enacted an ordinance that prohibited smoking in workplaces and indoor public areas, including bars and restaurants. For the study, researchers reviewed hospital admissions for heart attacks among area residents for one year prior to, and three years after the ban, and compared the data to two other nearby areas that didn't have bans (the part of Pueblo County outside city limits, and El Paso County, which includes Colorado Springs). Researchers found that during the three years after the ban, hospital admissions for heart attacks dropped 41 percent inside the city of Pueblo, but found no significant change in admissions for heart attacks in the other two control areas.

Eight studies done prior to this one in other locales used similar techniques and yielded similar results, but covered shorter periods of time -- usually about one year after the smoking ban went into effect. The results of this longer, more comprehensive study support the view that not only does secondhand smoke have a significant short-term impact on heart function, but that lives, and money, are probably being saved by new laws proliferating around the world in recent years that minimize public exposure to secondhand smoke.

Tobacco Smoke and the Heart

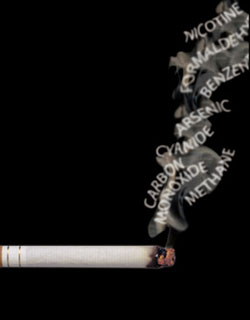

When most people think "cigarette smoke," they immediately think "lung cancer," but far less public attention has been paid to how secondhand smoke effects heart function. In a memo dated 1980 that I first discovered in 1999, a Philip Morris scientist points out that nicotine lowers the heart's threshold to ventricular fibrillation -- an inefficient heart pumping pattern -- which increases people's susceptibility to heart attacks.

When most people think "cigarette smoke," they immediately think "lung cancer," but far less public attention has been paid to how secondhand smoke effects heart function. In a memo dated 1980 that I first discovered in 1999, a Philip Morris scientist points out that nicotine lowers the heart's threshold to ventricular fibrillation -- an inefficient heart pumping pattern -- which increases people's susceptibility to heart attacks.

A 1991 report sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that secondhand smoke kills approximately 53,000 Americans year, mostly from heart disease. A public health study published in 2001 showed that exposure to secondhand smoke for even short periods of time, as little as 30 minutes, causes changes in platelets and cardiac epithelium. Lung cancer takes many years to develop, but heart function is impacted more rapidly upon exposure to secondhand smoke.

Tobacco Companies Have Long Been Aware of Secondhand Smoke Hazards

Tobacco companies knew much more about the health hazards of secondhand smoke, and knew it longer ago, than most people realize.

Recognizing the need to do more biological research on its own products, but also understanding the need to distance itself from this research for legal reasons, in 1971 Philip Morris purchased a biological lab in Germany called Institut Fur Biologische Forschung ("INBIFO"), or Institute for Biological Research. PM then created a complex routing system to ensure that work done at INBIFO could not be linked back to Philip Morris. INBIFO routed its study results through a PM research and development facility in Switzerland called Fabriques de Tabac Reunies, and documents created at INBIFO were often in French or German language.

Between 1981 and 1989, Philip Morris (PM) conducted at least 115 different inhalation studies on secondhand smoke at INBIFO in which they compared the toxicity of mainstream smoke (the smoke the smoker himself inhales) to that of secondhand smoke. PM discovered that secondhand smoke is 2-6 times more toxic and carcinogenic per gram than mainstream smoke. The company never published the results of these in-house studies or alerted public health authorities to their findings. Rather, they kept this information strictly to themselves -- even most Philip Morris employees were unaware of these studies.

Strategies to Deceive the Public

But Philip Morris did much worse than hide this crucial information from the public. Spurred by a 1993 EPA Risk Assessment that declared secondhand smoke a known human carcinogen, and recognizing the danger the secondhand smoke issue held for the cigarette industry, Philip Morris masterminded a massive global effort to confuse and deceive the public about the health hazards of secondhand smoke and to delay laws restricting smoking in indoor public places.

A 1993 internal Philip Morris (PM) strategy paper titled "ETS (Environmental Tobacco Smoke) World Conference" shows PM organizing a wide range of strategies to shape public views on secondhand smoke and fight smoking restrictions worldwide. PM pursued tactics to "shift concern over ETS to slippery slope argumentation and/or tolerance"; liken secondhand smoke to perceived risks from other items of public concern, such as cellular phones and chlorinated water; "shift concern over ETS in the workplace from the health issue to one of annoyance;" "shift the concern over ETS in restaurants from bans to accommodation where bans are imminent;" "develop an 'ETS Task Force,' with global PM representation to develop strategies to combat smoking restrictions;" "... package comprehensive improvements in ventilation to forestall tobacco specific bans and ... shift the debate from ETS to IAQ [indoor air quality]." Another strategy was the "development of a global coalition against "junk science" to complement a similar coalition PM was already forming in the United States.

At the same time, PM implemented Project Brass, a secret action plan conceived by the Leo Burnett Company, to create a "controversy" over secondhand smoke where there really was none. Project Brass strove to "forestall further public smoking restrictions/bans," "create a decided change in public opinion," and "develop an atmosphere more conducive to smokers" in the general public.

Project Brass was just the tip of the iceberg. The tobacco industry implemented many projects over the decades to shape public perception about secondhand smoke and to delay laws regulating it. Many of these projects are listed under TobaccoWiki's "Projects and Operations" page: Project Mayfly, the INFOTAB ETS Project, PM and British American Tobacco's Latin American ETS Consultants Program, PM's ETS (Environmental tobacco smoke) Media Strategy, Philip Morris' Science Action Plan, and PM's ICD-9 Project to impede the creation of a medical billing code that would indicate illnesses that are attributable to secondhand tobacco smoke exposure.

These are just some of the projects we've learned of by combing through industry documents. Any one of these projects taken individually would be stunning in scope and ambition in its own right, but all of them taken together -- and the as-yet undiscovered efforts -- probably constitute the single most coordinated, widespread, expensive, under-the-radar PR campaign ever waged.

These extensive, expensive and hidden deceptions significantly undermined public understanding of the hazards of secondhand smoke and killed thousands and thousands of non-smokers and smokers alike.

The Final Chapter?

The Pueblo study was only made possible because the people of Pueblo courageously enacted a smoke-free law before the rest of the state did. Pueblo's law predated Colorado's statewide smoking law by three years. This is how it usually happens: a slew of cities and towns enact their own smoking bans until finally a measure is passed at the state level. Attaining smoke-free places has been a true grassroots activity. Once people experience air clean of cigarette smoke in bars, restaurants and other public places, they love it and don't want to go back to allowing smoking. There are many people alive today who could never conceive of encountering cigarette smoke on buses or airplanes, in hospitals, theaters or universities or other places where once smoking was the norm. Once upon a time, most people believed it was impossible to get bars to go smoke-free, but today this commonsense life-saving law that is the norm in many states and countries.

Time and society are marching on, and as more people are protected from secondhand smoke, we are only starting to learn the true scope of its health effects -- from studies like the one done in Pueblo.

Comments

WoodstockLibertarian replied on Permalink

Subverting the math.

Mutternich replied on Permalink

WoodstockLibertarian

GDWilliams replied on Permalink

Watch your tongue. You'll be mistaken for one of "them"!

GDWilliams replied on Permalink

???

Mutternich replied on Permalink

'Just because the public is invited...'

WoodstockLibertarian replied on Permalink

Interpreting sarcasm..

Mutternich replied on Permalink

So now it's down to bars?

Oto replied on Permalink

Change welcome

Iro replied on Permalink

A little late to the party

GDWilliams replied on Permalink

The evidence is overwhelming

Pages