As reporters and researchers know all too well, releasing information isn't necessarily the same thing as releasing useful information.

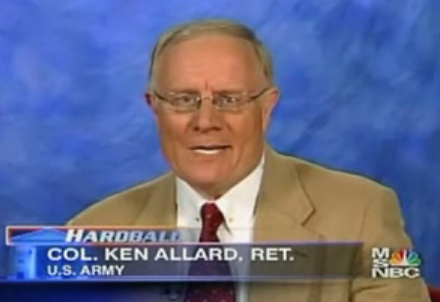

Case in point: the Pentagon's military analyst program. In early 2002, the Defense Department began cultivating "key influentials" -- retired military officers who are frequent media commentators -- to help the Bush administration make the case for invading Iraq. The program expanded over the years, briefing more participants on a wider range of Bush administration talking points, occasionally taking them overseas on the government's dime.

Case in point: the Pentagon's military analyst program. In early 2002, the Defense Department began cultivating "key influentials" -- retired military officers who are frequent media commentators -- to help the Bush administration make the case for invading Iraq. The program expanded over the years, briefing more participants on a wider range of Bush administration talking points, occasionally taking them overseas on the government's dime.

In April 2006, the group was used to counter criticism of then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. The apparent coordination between the Pentagon and the pundits piqued the interest of New York Times reporters. Two years later -- after wresting some 8,000 pages of internal documents from the Defense Department -- the Times exposed the Pentagon's covert attempts to shape public opinion through its so-called "message force multipliers." A few weeks later, the Defense Department posted the same documents publicly.

It wasn't the high-octane data dump it first appeared to be. Sure, paging through the emails, slides and briefing papers is interesting, and occasionally you come across something noteworthy. But the documents are formatted in such a way that systematically exploring them via keyword searches is impossible. A cynic (or realist) might think the Pentagon was doing damage control by putting the documents out in the open, while making it near-impossible to find crucial needles in a very large, chaotically-compiled haystack.

Case in point: the

Case in point: the  Over the next week, campaigners from around the United Kingdom will

Over the next week, campaigners from around the United Kingdom will

For the

For the  Nominations are now open for the

Nominations are now open for the