Submitted by Mary Bottari on

Almost two years after the Wall Street meltdown collapsed the economy and threw 8 million Americans out of work, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission gets underway January 19th in Washington, D.C.

Almost two years after the Wall Street meltdown collapsed the economy and threw 8 million Americans out of work, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission gets underway January 19th in Washington, D.C.

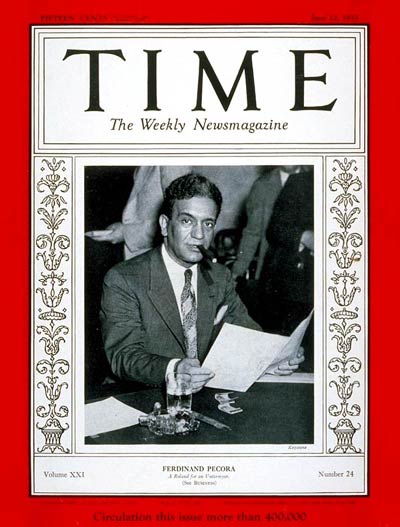

Will there be a new Ferdinand Pecora to get to the bottom of things?

Who is Ferdinand Pecora?

In the aftermath of the devastation of the 1929 stock market crash, some in Congress wanted answers. In 1933, the Senate banking committee launched an investigative commission to ferret out the fraud and corruption that led to the Great Depression. It hired a former Manhattan Assistant District Attorney with experience in financial crimes, Ferdinand Pecora, as its chief counsel.

Historian Ron Chernow described Pecora for the New York Times:

Born in Sicily, the son of an immigrant cobbler, Pecora had campaigned for Teddy Roosevelt and been imbued with the crusading fervor of the Progressive Era. As a prosecutor in the 1920s, he had shut down more than 100 'bucket shops' — seamy, fly-by-night brokerage houses — and this had tutored him in the shady side of Wall Street.

With black eyes, dark curly hair and a penchant for chomping on cigars, Pecora cut a colorful figure. He is credited for popularizing the term "Bankster" of which this site is so fond. But more importantly, he was driven and meticulous. He showed no mercy for the Wall Street titans he put on the stand, which included the scions of American banking, Morgans, Rockefellers and Lamonts.

Pecora's staff was a slice of America and included an Irish-American journalist by the name of John Flynn and Max Lowenthal, a Jewish lawyer. Flynn later wrote: "I looked with astonishment at this man who, through the intricate mazes of banking, syndicates, market deals, chicanery of all sorts, and in a field new to him, never forgot a name, never made an error in a figure, and never lost his temper."

The vigorous Pecora commission interviewed hundreds, including financial magnates, their underlings, brokers and analysts, compiled 12,000 pages of testimony and paved the way for a major financial services overhaul. The 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, the 1934 Securities and Exchange Act and other legislation protected the economy for the next 60 years. When these reforms unraveled in the 1980s and 1990s, the ground was laid for a "boom and bail" economy.

Who is Investigating the Current Meltdown?

The new Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, authorized by Congress in 2009, is charged with investigating causes of the meltdown, including mortgage fraud, capital and leveraging requirements, lending standards, derivatives, shady accounting practices and regulatory capture. It's also instructed to examine the causes of the collapse of the major financial institutions that failed, as well as those that survived with taxpayers' help.

Will the new investigative commission produce a new Pecora? It's possible. There are standouts among its members, including the Brooksley-born, ex-chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. She was lauded for foreseeing the problem with black book derivatives trading in the 1990s, but was famously shot down by Larry Summers, then undersecretary at Treasury, now top White House adviser. Former U.S. Senator Bob Graham (D-Florida) also showed his independence and distinguished himself when, as the head of the Senate Intelligence Committee, he was the only member of that committee to vote against the war in Iraq. The chairman, Phil Angelides, served as California State Treasurer from 1999 to 2007. He was well-known for pushing for disclosure and transparency for investments by CalPERS, the $200 billion state pension fund, and for threatening to stop giving state business to Wall Street firms that didn't meet conflict-of-interest standards.

A vigorous independent inquiry could fill the void left by the abject failure of the criminal justice system to hold the biggest Wall Street firms accountable. The Justice Department and the FBI have been so slow to bring prosecutions that state attorneys general have been left to pick up the slack and bring major cases against credit rating agencies, big banks and mortgage firms. But the commission's challenges are steep. It will have to avoid the usual Washington pitfall of an unworkable partisan divide. It will also only have one year to undertake its inquiry. Its final report is due in December of 2010.

The Commission and its Mission

When the commission was formed, Angelides told the Los Angeles Times: "Here's the big picture. The commission's role is to be a pursuer of the truth. If we commit ourselves to pursuing the facts and uncovering whatever is underneath whatever rock, we will do Americans a great service. And hopefully avoid this kind of thing happening again in the foreseeable future."

Angelides struck just the right note, but much work lies ahead for the commission to fulfill this promise. Today, almost two years after the crash, no employee of any major American financial institution is behind bars. If the commission fails to defrock the high priests of finance and expose the deception of consumers, rampant accounting fraud and the complicity of regulators, they will have betrayed the American taxpayer and failed their historic mandate of preventing the next crisis.

For a full list of Financial Inquiry Commission members, their professional and political associations see Bloomberg News, California's Angelides to Lead Financial Crisis Probe.

Comments

memento58 replied on Permalink

It will also only have one

macoy replied on Permalink

brilliant Pecora