Submitted by Brendan Fischer on

-- by Brendan Fischer and Lisa Graves

You've probably heard of the billionaire Koch Brothers by now, and their sinister push to distort our democracy. But you may not have heard of Rex Sinquefield.

You've probably heard of the billionaire Koch Brothers by now, and their sinister push to distort our democracy. But you may not have heard of Rex Sinquefield.

Unlike the Koch Brothers, who made their money the old-fashioned way, by inheriting it, Sinquefield is a self-made man, who earned a fortune in the stock market by investing in index funds.

He's a major funder of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), and he has also bankrolled the Club for Growth.

Though he was born in Missouri, he didn't move back there until 2005, after being away nearly four decades.

Now he claims to know how to "fix" the state. To an astonishing degree, over the last few years, Missouri's political landscape has been dominated by the wish list of just this one man.

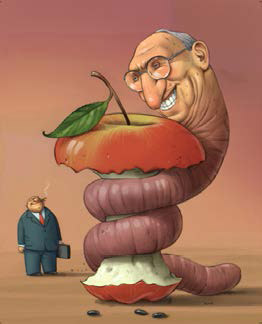

Sinquefield is doing to Missouri what the Koch Brothers are doing to the entire country. For the Koch Brothers and Sinquefield, a lot of the action these days is not at the national but at the state level.

By examining what Sinquefield is up to in Missouri, you get a sobering glimpse of how the wealthiest conservatives are conducting a low-profile campaign to destroy civil society.

Sinquefield told The Wall Street Journal in 2012 that his two main interests are "rolling back taxes" and "rescuing education from teachers' unions."

His anti-tax, anti-labor, and anti-public education views are common fare on the right. But what sets Sinquefield apart is the systematic way he has used his millions to try to push his private agenda down the throats of the citizens of Missouri.

Our review of filings with the Missouri Ethics Commission shows that Sinquefield and his wife spent more than $28 million in disclosed donations in state elections since 2007, plus nearly $2 million more in disclosed donations in federal elections since 2006, for a total of at least $30 million.

Sinquefield is, in fact, the biggest spender in Missouri politics.

In 2013, Sinquefield spent more than $3.8 million on disclosed election-related spending, and that was a year without presidential or congressional elections. He gave nearly $1.8 million to Grow Missouri, $850,000 to the anti-union teachgreat.org, and another $750,000 to prop up the Missouri Club for Growth PAC.

However, these amounts do not include whatever total he spent last year underwriting the Show-Me Institute, which he founded and which has reinforced some of the claims of his favorite political action committees. The total amount he spent on his lobbying arm, Pelopidas, in pushing his agenda last year will never be fully disclosed, as only limited information is available about direct lobbying expenditures. Similarly, the total amount he spent on the PR firm Slay & Associates, which works closely with him, also will not ever be disclosed. These are just a few of the tentacles of his operation to change Missouri laws and public opinion.

Even more revealing is how Sinquefield behaved when Missouri was operating under laws to limit the amount of donations one person or group could give to influence elections. In order to bypass those clean election laws, he worked with his legal and political advisers to create more than 100 separate groups with similar names. Those multiple groups gave more, cumulatively, than Sinquefield would be able to give in his own name, technically complying with the law while actually circumventing it. That operation injected more than $2 million in disclosed donations flowing from Sinquefield during the 2008 election year, and it underscored his chess-like gamesmanship and his determination to do as he pleases. (Sinquefield is an avid chess player.)

Shortly after that election, the Missouri legislature repealed those campaign finance limits, with his backing. Those changes benefited Sinquefield more than anyone. As a result, in 2010, Sinquefield made disclosed political donations more than ten times greater than what he spent in 2008.

His disclosed election spending reveals that he is focusing his efforts on remaking Missouri's legislature and laws. But in 2012 he did make some federal donations, including $1 million to the Now or Never PAC, plus $100,000 to Karl Rove's American Crossroads PAC, plus small sums to almost every Republican presidential candidate that year. Sinquefield also gave money to some extreme Congressional candidates, including Michele Bachmann, Todd Akin of the infamous "legitimate rape" quote (after the other candidate Sinquefield backed lost in the primary), and Ted Cruz.

In Missouri, Sinquefield's strategy has been to focus on a few issues dear to him.

First, he spent lavishly to try to prohibit some cities in the state from imposing an income tax. He shelled out more than $11 million underwriting the "Let Voters Decide" ballot proposition in 2010, which won by a two-to-one margin. He spent about $8.67 a vote.

The proposition required Kansas City and St. Louis to hold a referendum on whether to keep the municipal income tax in 2011, and every five years after that. To Sinquefield's dismay, in April 2011, citizens voted overwhelmingly to keep taxing themselves, with 78 percent in favor in Kansas City and 87 percent in St. Louis.

But he hasn't given up.

Now Sinquefield is trying to do away with the 6 percent state income tax. Doing so would enrich him personally, since the investment firm he co-founded still manages more than $200 billion in investments, some of which he may still own. Plus, if the business is ever sold, he stands to make a windfall.

To help replace lost revenue from the income tax, Sinquefield favors an increase in the sales tax (and a broadening of it to include such things as child care). A study he commissioned also recommends increased taxes on "restaurants, hotels, cigarettes, and beer," while "shift[ing] the major tax burden from companies and affluent individuals," like Sinquefield. And it recommends selling off the public's assets, like the St. Louis airport, trading a short-term infusion of revenue in exchange for giving for-profit corporations access to decades of revenue.

He doesn't want an increase in property taxes. Can you blame him? He has a 22,000-square-foot house on an estate of hundreds of acres in the Missouri Ozarks, and another home in St. Louis worth at least $1.78 million, replete with a private elevator. He also owns a lot of cars, including a 2008 Bentley Continental Flying Spur that retailed for $170,000.

Sinquefield's taxation proposals would necessitate cuts in the state's provision of services many people take for granted as part of living in a modern, civil society: public education, public libraries, and other public goods.

Sinquefield did not respond to a request for comment on this article.

Nowhere are Sinquefield's destructive intentions clearer than in his campaign against public education.

"I hope I don't offend anyone," Sinquefield said at a 2012 lecture caught on tape. "There was a published column by a man named Ralph Voss who was a former judge in Missouri," Sinquefield continued, in response to a question about ending teacher tenure. "[Voss] said, ‘A long time ago, decades ago, the Ku Klux Klan got together and said how can we really hurt the African American children permanently? How can we ruin their lives? And what they designed was the public school system.' "

Sinquefield's historically inaccurate and inflammatory comments created a backlash from teachers, public school advocates, and African American leaders, who called it "a slap in the face of every educator who has worked tirelessly in a public school to improve the lives of Missouri's children."

The statement would be easy to write off as buffoonery if it didn't come from Sinquefield, who has poured millions from his personal fortune into efforts to privatize education in the state through voucher programs and attacks on teacher tenure.

The jewel in his privatization crown is the Missouri-based Show-Me Institute, a rightwing think tank that receives just shy of $1 million every year from the Sinquefield Charitable Foundation. Its tag line is a mouthful: "Advancing Liberty with Responsibility by Promoting Market Solutions for Missouri Public Policy."

Rex Sinquefield is the institute's president, and his daughter is also employed there (and spends her time tweeting rightwing talking points). The institute is currently led by Brenda Talent, the wife of former U.S. Senator Jim Talent.

For years, the institute has been laying the groundwork for radical changes to Missouri's education system, producing reports, testimony, and policy papers purporting to show the benefits of ending teacher tenure and enacting vouchers in the form of "tuition tax credits," along with other efforts to privatize education and undermine teachers' unions.

The Show-Me Institute does not act alone. It is a member of ALEC, and many of the education initiatives it promotes appear to have their roots in ALEC "model" legislation, such as tuition tax credits, parent trigger legislation, and attacks on union rights.

The Speaker of the Missouri House, Tim Jones, is a member of the ALEC Education Task Force and for many years has been the ALEC state chair for Missouri.

Sinquefield bankrolled Jones's 2012 campaign to the tune of $100,000. Not that Jones needed the money; he was running unopposed that year.

Jones has made it clear he is an ally of deep-pocketed interests. He is quoted in ALEC's promotional materials as saying the benefit of ALEC is that "business leaders have a seat at the table."

Together, Jones and the Show-Me Institute—backed with Sinquefield cash, and using ALEC model legislation—have pushed an education privatization agenda in the state.

For example, Speaker Jones sponsored "parent trigger" legislation in both 2011 and 2012, bills that reflected the ALEC model "Parent Trigger Act." Parent triggers allow parents to vote via referendum to seize control of their public schools and fire the teachers and principal or privatize the schools. The Show-Me Institute provided outside support for the legislation, with a group's representative claiming that the bill "would expand the ability of parents to take an active role in the public education of their children."

Parent triggers are presented as a grassroots way to give parents control—and have been romanticized in the film Won't Back Down— but Diane Ravitch, an education historian and former U.S. assistant secretary of education in the first Bush Administration, characterizes parent trigger laws as a "clever way to trick parents into seizing control of their schools and handing them over to private corporations."

It doesn't end there. In 2008, the Show-Me Institute released a "policy study" titled "The Fiscal Effects of a Tuition Tax Credit Program in Missouri," and that same year, Jones introduced a tuition tax credit bill titled the "Children's Education Freedom Act," which reflected the ALEC "Great Schools Tax Credit Act." (Despite the Show-Me Institute study claiming to demonstrate that tuition tax credits would save the state money, the bill's fiscal note estimated the cost at $40 million.)

In contrast with traditional vouchers, where the state directly reimburses a private school for tuition costs, these "tuition tax credit" proposals—sometimes called neo-vouchers—offer tax credits to individuals and corporations who donate to a nonprofit "school tuition organization." The nonprofit then pays for a student's tuition.

The Missouri state constitution's strict separation of church and state requires that those seeking to privatize education do so via these neo-vouchers. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, the Missouri constitution bars the use of any public funds in support of religious institutions, including schools.

The appeal of neo-vouchers is that the funding for a religious school's tuition doesn't come directly from the state; it comes from the nonprofit "school tuition organization." Even though the nonprofits are funded by tax credits, proponents argue that neo-vouchers wouldn't violate the state constitution's ban on taxpayer funds for religious institutions.

Having failed to fulfill their agenda in the legislature on the voucher issue, Sinquefield and his allies are now turning to the ballot initiative process.

At the end of 2013, a newly formed group called Missourians for Children's Education—backed with $300,000 from the Catholic Church, and with the support of the Show-Me Institute—began circulating petitions to put a tuition tax credit measure on the ballot this year.

The proposal would allow for a 50 percent tax credit for donations to scholarship-granting organizations, and up to $90 million in credits earned annually. Apparently in response to the failure of past tuition tax credit efforts, the proposal reserves 50 percent of the tax credits for organizations spending on public school districts, 40 percent for private and religious schools, and 10 percent to special education in either private or public schools.

"This one is deliberately appealing to [public school supporters]," James Shuls, an education analyst with the Show-Me Institute, told the Heartland Institute. "‘Look, you're getting the bulk of these funds. This proposal might get opposition, but not as much opposition" as other privatization measures.

Sinquefield is also pouring some of his fortune into an effort to take tenure away from teachers.

"Can you think of any other occupation where you can screw up—and screw up children's lives permanently—and they can't fire you?" Sinquefield asked in 2012.

Contrary to the claims of the billionaires and millionaires, tenure doesn't guarantee a teacher a job; it instead guarantees that teachers have the right to due process. It protects teachers from being fired for political or personal reasons, and deters administrators from firing experienced (and higher-paid) teachers to replace them with less experienced (and less expensive) teachers, which might be good for the budget, but is usually bad for kids.

Republican legislators and Sinquefield-backed groups have long pushed "reforms" to tenure. But after years of legislative failures, Sinquefield and a group he funds, the Children's Education Council of Missouri, are now turning to a statewide ballot initiative.

In the last two years, Sinquefield has given at least $925,000 to teachgreat.org, which was organized to promote the teacher-tenure initiative petition. That initiative would require a constitutional amendment mandating a three-year limit on teacher contracts and requiring that teachers be "dismissed, retained, demoted, promoted, and paid primarily using quantifiable student performance data."

Teachgreat.org aims to collect 160,000 signatures to get the tenure measure on the ballot this year. Sinquefield also backed a similar ballot initiative two years ago that failed to collect enough signatures.

Incidentally, Missouri already has more stringent tenure standards than every other state besides Ohio. A teacher has to work for five years before becoming eligible for tenure; in forty-two other states, tenure can kick in after three years or less.

Harry Truman, Missouri's favorite son, once observed: "Wall Street, with its ability to control all the wealth of the nation and to hire the best law brains in the country, has not produced some statesmen, some men who could see the dangers of bigness and of the concentration of the control of wealth. . . . They are still using the best law brains to serve greed and self-interest. People can stand only so much, and one of these days there will be a settlement."

In Truman's own Missouri today, Rex Sinquefield epitomizes "the dangers of bigness and of the concentration of the control of wealth." Whether there will be a settlement is up to the citizens of the Show-Me State.

This article was originally published in the May 2014 issue of The Progressive magazine.

Read more about Sinquefield in the "Reporters' Guide to Rex Sinquefield and the Show-Me Institute" from Center for Media and Democracy and Progress Now.

Comments

Jerry Ryberg replied on Permalink

Rex Sinquefield

Public employee replied on Permalink

Rex Sinquefield and the sad state of Missouri

F Mason replied on Permalink

A Missouri Voter

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Your bias is disgusting. How

St. Charles Co ... replied on Permalink

Wow - Can You Say Biased

Deb replied on Permalink

WOW

Pam Gevecker replied on Permalink

You are so far off in your

Mark Stump replied on Permalink

Rex Sinquefield is my hero

Leading Edge Boomer replied on Permalink

Sinquefield bankrolls Paul Ryan's political empire