Submitted by Jonas Persson on

Twenty-five years ago, Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson signed the nation's first school voucher bill into law. Pitched as social mobility tickets for minority students, Wisconsin vouchers allow children to attend private, and sometimes religious, schools on the taxpayers' dime.

But as shown by the murky history of the voucher movement, and by the way voucher programs have developed in Wisconsin and other states, racial equity had nothing to do with it. It was a scheme cooked up out of an ideological disdain for public schools and teachers' unions, and first used to actually preserve school segregation in the South.

Today, vouchers bills are on the move in multiple states and on Capitol Hill. GOP presidential hopefuls, who want to boost their free market bona fides for a 2016 run, have been outbidding themselves in touting vouchers as educational panaceas that will not only help minority children close education gaps, but cut corporate and property taxes in the process.

A Nationwide Voucher Program?

On April 15, Rand Paul (R-KY) introduced an amendment to an omnibus education bill that would have spelled the end to federal education aid as we know it.

Under the amendment to the Senate bill, which is a revamp of the No Child Left Behind Act, federal Title I dollars, intended to support public schools with a high proportion of low-income students, would instead follow individual students even if they choose to attend private schools.

This would have paved the way for a multi-billion-dollar nationwide voucher system, siphoning money from public school districts to private and  possibly religious schools that—unlike their public counterpart—have no obligation to serve minority, at-risk or special-needs students. These schools are also free to ditch the science curriculum in favor of climate-denial and creationism.

possibly religious schools that—unlike their public counterpart—have no obligation to serve minority, at-risk or special-needs students. These schools are also free to ditch the science curriculum in favor of climate-denial and creationism.

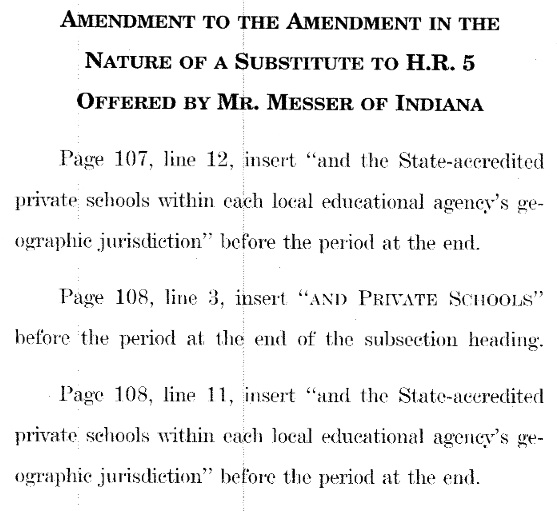

A few months earlier, Congressman Luke Messer (R-IN) bused a bunch of kids to the Capitol to celebrate "National School Choice Week." Among the speakers were Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) and House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH). Their enthusiasm, however, was somewhat dampened by the kids who—for all Messer's emceeing—seemed ill at ease with being displayed as placard-wearing pawns in a political game.

Precisely what kind of school choice Messer had in mind became clear when he introduced a voucher amendment to the House version of the bill. Both Messer and Paul chose to withdraw their respective amendments, but introducing them in the first place is a way of flexing their muscles. Vouchers are gaining traction and Messer, who chairs the Congressional School Choice Caucus, has vowed not to rest until "every kid in America has that kind of opportunity."

GOP Presidential Hopefuls Hail Vouchers as Miracle Cures

Rand Paul's and Luke Messer's attempts to direct federal taxpayer money to private schools comes in the wake of a massive push for school vouchers. In 2013, Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) introduced an "Educational Opportunities Act" which would have created a voucher-like system allowing children from low- or middle-income families to attend private schools funded through tax-deductible corporate and private donations. The businesses get the write-off and taxpayers lose out on public revenue.

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie has implemented a slew of school “reforms,” including an expansion of the state’s charter school program and a new law making it easier to fire tenured teachers. But he now has his eyes set on vouchers, or what he calls “opportunity scholarships,” as well.

Others have upped the ante. Louisiana’s Republican Governor Bobby Jindal created the largest voucher program in the nation in 2012 with the hope of enrolling 380,000 K-12 students in private and religious schools. It was later struck down as unconstitutional by the state supreme court. “[S]tate funds … cannot be diverted to nonpublic schools … according to the clear, specific and unambiguous language of the constitution,” the court wrote in its ruling. The North Carolina and Alabama voucher programs were ruled unconstitutional on similar grounds by courts last year.

Not one to be outdone by his fellow presidential contenders, Republican Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin recently announced he would lift the 1,000-student cap on the statewide voucher system. And even though the Wisconsin Constitution has a similar “public purpose doctrine,” which does not allow taxpayer money to fund a “private purpose,” the original Milwaukee voucher program has already survived multiple court challenges. Chances are that Walker (if given the go-ahead by the GOP-controlled legislature) will prevail in creating the largest voucher program in the nation.

A Trojan Horse in Wisconsin and Elsewhere

As ground zero for school vouchers, and the first state to enroll religious schools in the program, Wisconsin is worthy of closer scrutiny. Walker’s sweeping expansion was unveiled in his 2015 budget address. Denounced by both local and national media as “a serious threat to local education” (The Post Crescent) and part of “a clumsy attack on education” (The New York Times) the proposal was "applauded" by the American Federation for Children, the lobby powerhouse linked to the billionaire DeVos family and their ideological crusade to destroy the public education system as we know it. In 2011, AFC greased the skids for Walker with a $1.1 million issue-ad buy while he faced recall for having all but destroyed collective bargaining rights for teachers and public sector employees.

“Every child,” Walker said in his address, “deserves to succeed.” It’s an empty sound bite, but it’s also a surprisingly revealing one. Wisconsin school vouchers were never meant for everyone; this was part of their appeal. When introduced in Milwaukee in 1990, they were pitched as social mobility tickets, and they were restricted to students from families earning less than 175 percent of the federal poverty level.

The program was championed by some prominent African-American community leaders and lawmakers, such as Dr. Howard Fuller and Annette “Polly” Williams, a Democrat from Milwaukee who went on to travel the country rallying support for “school choice.”

But what happened once the system was in place soon drew the ire of its early supporters. Under Walker, the income requirement for Milwaukee was upped to 300 percent of the poverty level. A married couple with two children can currently earn $78,637—far more than the median U.S. family income of $52,250—and still send them off to private schools at the public's expense. Polly Williams put it bluntly in a 2013 interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: "They have hijacked the program."

In fact, what happened in Milwaukee is far from unique. Other states have introduced vouchers as "civil rights" measures only to expand the programs to higher-income white families. The voucher-like corporate tax credit program in Georgia was originally billed as a way of helping African-American and Latino families, but most scholarships have been awarded “white students from upper income families,” the Southern Education Foundation wrote in a scathing report.

In 2013, Governor Mike Pence of Indiana raised the income requirements of the voucher program in the Hoosier State, and last year, Florida's Republican governor Rick Scott lifted the income bar for the state voucher program, allowing a family of four making up to $62,010 a year to participate—$20,000 higher than the previous limit.

While the statewide voucher program in Wisconsin is so far limited to students from families making less that 175 percent of the federal poverty level, just like the Milwaukee program in its infancy, school advocates are worried that we will once again see a gradual "easing" of the requirements.

Subsidizing Segregation?

What emerges is a pattern of limited voucher programs signed into law under the promise of helping minority children, but later expanded to subsidize more affluent white families. What are the consequences?

As universal voucher programs are still some way off, there is no empirical data. But a 2006 study published by the University of Connecticut takes a novel approach in answering the question. By analyzing voter patterns when vouchers were on the ballot in California, the authors conclude that “among white households with children, support for voucher increases with the proportion of minority students in the local public schools. This is not true of non-white households."

In other words, as more middle class families are free to enroll their kids, self-segregation with white children drawing taxpayer money to attend racially homogenous private schools could take off. The possibility deeply concerns education experts.

“The question is: are we comfortable using our tax dollars to subsidize those choices?" Julie Mead, professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at UW-Madison, told CMD.

The Racial History of School Vouchers

The history of the voucher movement is seldom told, least of all by its advocates. But it is a history well worth telling, and it might give some idea of where we are headed.

Concern for minorities was never part of the original design. It was a libertarian scheme cooked up out of an ideological hostility toward the idea of public schools. And more tellingly, vouchers were first used to flout desegregation laws.

Early supporters would time and again find themselves faced with a dilemma: should they support public desegregated schools or private ones—including those discriminating on the basis of race? As it turned out, ideology trumped any concern for the children.

Until the mid-1980s, the school voucher movement remained a fringe movement of hardline libertarians and New Right ideologues—including the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC)—as well as religious school leaders. It also had some disturbing bedfellows thrown in for good measure, such as white supremacists keen on using vouchers to foster “white flight.”

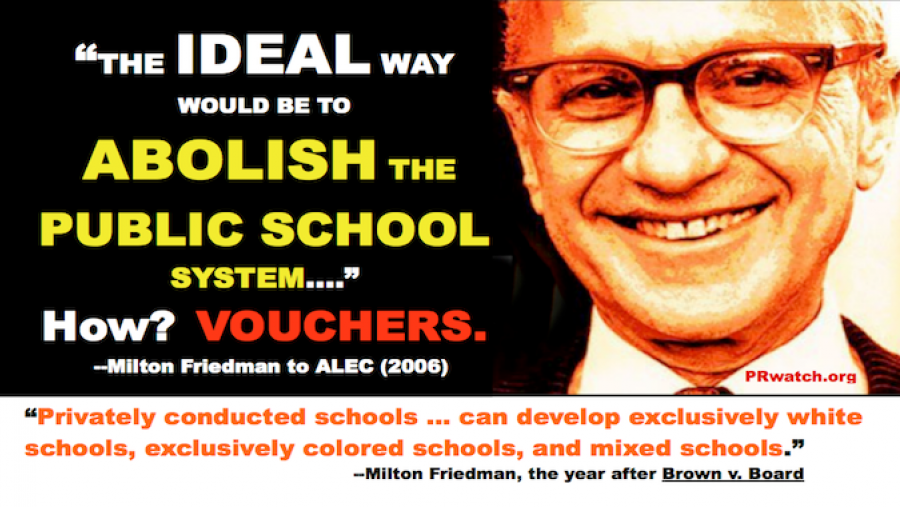

In fact, school vouchers first emerged as a policy prescription in the mid-1950s, just as the U.S. Supreme Court was ordering school desegregation in the Brown v. Board of Education series of decisions. While University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, who first floated the idea in a 1955 essay, wanted to see public schools turned into competing corporations on the free market, vouchers were de facto used in the South as a way to preserve segregation.

In fact, school vouchers first emerged as a policy prescription in the mid-1950s, just as the U.S. Supreme Court was ordering school desegregation in the Brown v. Board of Education series of decisions. While University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, who first floated the idea in a 1955 essay, wanted to see public schools turned into competing corporations on the free market, vouchers were de facto used in the South as a way to preserve segregation.

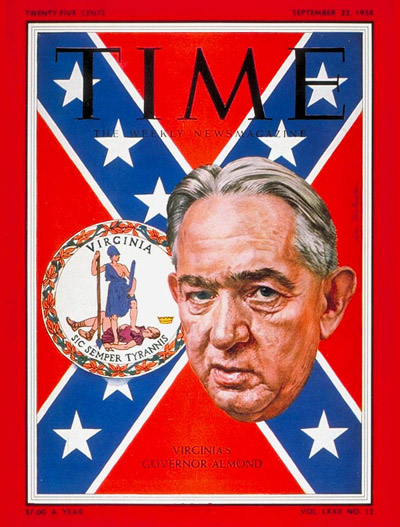

In 1959, for example, Virginia Governor Lindsay Almond introduced tax-funded tuition grants to white parents who wanted to send their children off to private schools that were not subject to the desegregation laws.

When Friedman learned of this, he found himself between the rock of public school segregation by law and the hard place of state intervention. He embraced racially segregated schools as a benefit of the free market while “So long as the schools are publicly operated, the only choice is between forced nonsegregation and forced segregation; and if I must choose between these evils, I would choose the former as the lesser. Privately conducted schools can resolve the dilemma ... Under such a system, there can develop exclusively white schools, exclusively colored schools, and mixed schools."

For many years “school choice was widely understood by the courts and the public as a strategy to preserve school segregation,” education historian Diane Ravitch writes. In the 1970s, rightwing ideologues (often allied with religious school leaders, and entrepreneurs eager to cash in on the new market) fought an uphill battle.

The first known statewide attempt to introduce a voucher system took place in Michigan where a shadowy group calling itself Citizens for More Sensible Financing of Education managed to put the question of voucher schools on the midterm ballot in 1978, but an overwhelming majority (74 percent) rejected the proposal.

The time was not yet ripe as many voters still recalled the segregationist roots of schools vouchers. Not to be deterred, however, the two engineers of the proposal—Richard McLellan and Robert Baldwin—would go on to fight for school privatization both in Michigan and nationwide.

McLellan, a Lansing attorney, later co-founded the rightwing Mackinac Institute and recently served as Governor Rick Snyder’s unofficial education advisor. In 2013, The Detroit News revealed how he had been meeting in secret with Snyder’s aides using code words to discuss how to smuggle a state voucher system in the back door.

Baldwin is less well known, but he acted as an advisor to ALEC and founded several Michigan and national advocacy groups hoping to enlist support for vouchers. He got more than he bargained for.

Strange Bedfellows

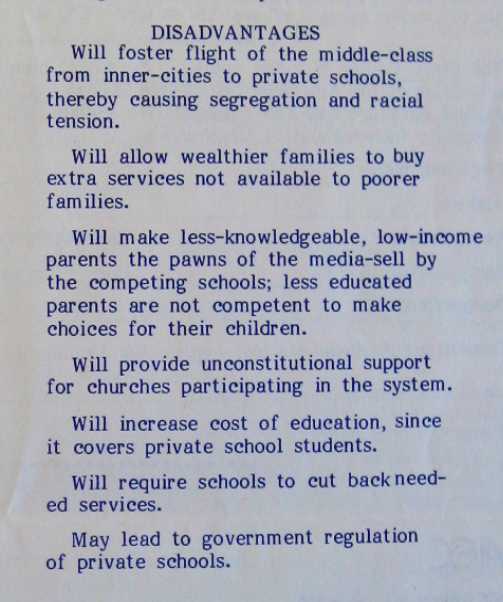

Viewing the result of the 1978 ballot proposal as a partial success, ALEC would go on to inundate lawmakers with a massive nationwide push toward private school vouchers in 1981. A voucher bill was sent to “16,000 state and federal officials, including every state legislator in the country,” ALEC boasted in the November 1981 issue of the internal newsletter The State Factor.

In a lengthy analysis of what the implications of school vouchers might be, ALEC admitted to a few disadvantages, such as ”flight of the middle-class from inner-cities to private schools, thereby causing segregation and racial tension.” But this, ALEC went on to argue, is more than made up for by the fact that vouchers are true to the principles of federalism by empowering individuals at the expense of government.

When President Ronald Reagan a year later announced plans to introduce a similar scheme of tuition-tax credits for families with children in private schools in an attempt to shore up Catholic support, voucher advocates from the “New Right,” including ALEC founder Paul Weyrich of the Moral Majority, were enthusiastic.

Under the plan, parents would be able to deduct half the cost of tuition directly from the federal income tax. But there was a rub. Many of them were worried that some schools, especially those discriminating on the basis of race, would be excluded from the plan.

“Although the conservative organizations oppose racial discrimination in education, the federal government should not punish schools that practice such policies by refusing to grant them tax-exempt status,” said Robert Baldwin, who worked on the Michigan proposal and was listed a "voucher contact" in the ALEC newsletter, in an interview with EdWeek.

Baldwin's tacit support for racial discrimination—following in the footsteps of Milton Friedman—was pitched as a concern about potential IRS harassment of religious schools, but others did not mince their words. A 1982 issue of the white supremacist magazine Instauration praised Baldwin's Voucher Institute, and the “racial nature of the crusade,” pointing out that the voucher movement drew most of its support from “white flight” areas.

As this example shows, the racial legacy of vouchers was still very much intact. Even some of the early proponents from the “New Right” were not averse to using the scheme to subsidize and perpetuate school segregation.

While Ronald Reagan had flirted briefly with the idea of funding private and religious K-12 education with taxpayer money (the proposal died before it reached the Senate floor), the school voucher movement remained on the fringe well into the 1980s.

ALEC continued peddling its ideological arguments. The main purpose of vouchers, the bill mill noted in a 1984 commentary to its original bill, is to "to introduce normal market forces" into education, and to "dismantle the control and power of" teachers' unions. While there is a narrative of parent "empowerment," there is not even a passing mention of children—let alone minority children.

But vouchers would soon gain a unique selling point.

The "New" Civil Rights Movement Is Born in a Staggering PR Coup

In their 1981 book Free to Choose, Milton Friedman and his wife Rose floated the idea of making a foray into African-American communities. Vouchers, they reasoned, could be pitched as a system that would "free the black man from dominion by his own political leaders."

As if hit by a collective wake-up call, voucher advocates suddenly realized that the pipe dream of a free market "utopia," where public schools and democratic school boards were consigned to the dustheap of history, could actually be realized. All it took was some posturing and a great deal of cynicism.

"In today's world," the rightwing quarterly The Public Interest suggested in a 1988 article, "those who would expand choice programs face many legal and political obstacles. Linking choice programs and integration may be their best bet." The New Right had, as The Black Commentator eloquently explained in a 2004 article, found its missing link:

Former Reagan Education Secretary William Bennett understood what was missing from the voucher political chemistry: minorities. If visible elements of the Black and Latino community could be ensnared in what was then a lily-white scheme, then the Right’s dream of a universal vouchers system to subsidize general privatization of education, might become a practical political project. More urgently, Bennett and other rightwing strategists saw that vouchers had the potential to drive a wedge between Blacks and teachers unions, cracking the Democratic Party coalition. In 1988, Bennett urged the Catholic Church to “seek out the poor, the disadvantaged…and take them in, educate them, and then ask society for fair recompense for your efforts”–vouchers. The game was on.

In the late '80s, conservative think tanks and advocacy groups across the nation launched massive whitewashing campaigns; they started churning out policy reports and books purporting to show how school vouchers would actually benefit minority students. Examples include: We Can Rescue Our Children: The Cure for Chicago's Public School Crisis (Heartland Institute, 1988) and Liberating Schools: Education in the Inner City (Cato Institute, 1990).

By proposing schemes with vouchers weighted to boost racial diversity, or restricted to children from low-income families, the organizations pushing vouchers were able to kill two birds with one stone. They made them acceptable by obscuring the segregationist history, and, crucially, they could now cast themselves as the "new" civil rights movement.

"It's an attempt to redefine what civil rights mean," Janelle Scott, associate professor at the Graduate School of Education & African Studies at UC Berkeley, told CMD. "In this version, it is all about individual empowerment, but is important to realize that the sum total of individual empowerment is collective empowerment, and this is where the argument doesn't hold."

As part of this ideological realignment, the advocacy groups advised voucher proponents to launch defamation campaigns against true civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP, accusing them of not caring about children and being in bed with the government and unions. The rightwing Heartland Institute outlined this new strategy in a 1991 report aptly titled "A Marketing Plan for Educational Choice."

"Abolish the Public School System"

The civil rights ploy proved remarkably successful. But 27 years later, with universal voucher programs on the horizon, the "integration" veneer is wearing thin.

In addition to lifting the cap on statewide vouchers, Scott Walker also wants to end the voluntary integration program known as Chapter 220, citing cost savings. The program, which dates from 1977, is designed to help integrate schools by allowing minority students from downtown Milwaukee to attend suburban schools while providing them with free transportation. At the same time, white suburban students are given incentives to enroll in schools downtown.

A 2013 study of the program concluded that, while the program has fallen short of ending segregation, it “has improved the racial composition of schools to increase the likelihood that all students receive an equal education.” Expanding vouchers while gutting an integration program that is all about choice might seem hypocritical. "From a political standpoint I'm baffled—I'm bewildered—that the governor says he wants to expand parental choice, but he's willing to phase out the state's first parental choice program," Demond Means, Superintendent of the Mequon-Thiensville School District, told Glendale Now in February.

But as the history of the voucher moment shows, "choice" was always predicated on parents choosing private—sometimes even segregated—schools. Vouchers were not proposed with equity in mind; they were cooked up out of an ideological disdain for public schools and teachers' unions.

While lecturing rightwing state lawmakers at a 2006 ALEC meeting, voucher engineer Milton Friedman posed the question: "How do we get from where we are to where we want to be?" The ideal way "would be to abolish the public school system." But alas, "you're not gonna do that." Dismantling public schools in one fell swoop would be political suicide, but introducing a universal voucher system, he explained to thunderous applause, is a politically more palatable way of reaching the same goal.

Here is a fuller transcript from Milton Friedman's ALEC speech:

If I were to ask everyone here, what would be your idea of the right way to conduct, to have an educational system constructed, you would say the ideal would be to have parents control and pay for their school's education, just as they pay for their food, their clothing and their housing. That, of course, would leave some indigent and problems of charity. Those should be handled as charity problems, not educational problems. The reason we can not do that is because taxes are used to pay not for education, but for schools, for teachers.

How do we get from where we are to where we want to be—to a system in which parents control the education of their children? Of course, the ideal way would be to abolish the public school system and eliminate all the taxes that pay for it. Then parents would have enough money to pay for private schools, but you're not gonna to do that. So you have to ask, what are politically feasible ways of solving the problem. The answer, in my opinion, is choice, that you have to change the way government money is directed. Instead of it being used to finance schools and buildings, you should decide how much money you are willing to spend on each child and give that money, provide that money in the form of a voucher to the parents of the children so the parents can choose a school that they regard as best for their child.

Comments

mademoiselle replied on Permalink

Yup

Geoffrey R Skoll replied on Permalink

vouchers

ciedie aech replied on Permalink

vouchers

Frank replied on Permalink

Great points about vouchers