Submitted by Sheldon Rampton on

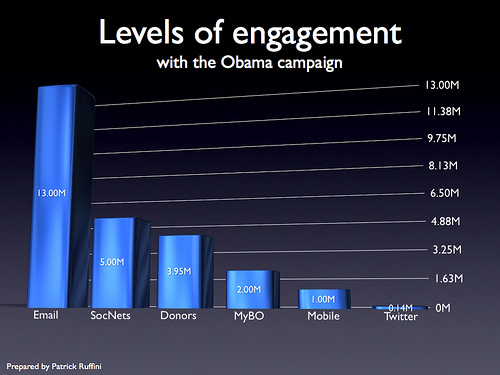

I've been following some of the recent writings of Patrick Ruffini, a former "eCampaign Director" for the Republican National Committee who is part of an effort to reinvent and reinvigorate the Republican Party in the United States. Ruffini is overall a fairly smart guy who is realistic enough to emphatically reject some of the more ridiculous conservative talking points. I've seen him write some astute analyses, particularly when writing about online political organizing.

I was struck, therefore, at the absence of all those positive qualities when Ruffini wrote a recent blog post that touched on topics related to what the government should actually do when it governs. The goal in politics, after all, is not simply to win elections but to wield power toward some purpose upon taking office. Ruffini's post, titled "The iPod Tax: This Is How We Win," suggests that he is searching for hot-button issues that will help conservatives win elections. Upon reading it, however, I came away thinking that the real problem facing conservatives is that they literally have no idea how to govern effectively, and little evident interest in learning.

Ruffini begins by criticizing New York governor David Patterson, who recently proposed to address his state's $15.4 billion budget gap by introducing a number of "tax increases on services people use every day -- like iTunes downloads and taxis." Ruffini sees the proposal as "a gift" to conservatives because it gives them "a ready-made issue" to campaign on, namely, "kill the iTunes tax."

Ruffini begins by criticizing New York governor David Patterson, who recently proposed to address his state's $15.4 billion budget gap by introducing a number of "tax increases on services people use every day -- like iTunes downloads and taxis." Ruffini sees the proposal as "a gift" to conservatives because it gives them "a ready-made issue" to campaign on, namely, "kill the iTunes tax."

Obviously, no one wants to pay more than they are currently paying for music on iTunes, so it isn't hard to imagine that people can be found who will complain about Patterson's proposal. However, let's think about this for a moment as an issue of actual governance rather than as an opportunity to incite emotion. Ruffini doesn't attempt to deny that New York is facing a $15.4 billion budget deficit, and he offers no suggestions for ways to deal with that deficit. The state of New York, of course, has no option but to deal with it. Unlike the federal government, state and local governments aren't allowed to print money, so they simply can't get away with running large budget deficits. This therefore leaves New York with only two options: raise more revenues (meaning taxes of some form), or reduce spending. If Ruffini were interested in how the state of New York should actually govern itself (instead of simply helping his party construct a campaign slogan), he would therefore need to balance his opposition to the iTunes tax with a list of services that New York should cut or eliminate. However, he either knows that there are no easy or popular cuts, or he prefers not to think that hard. He therefore simply recommends posturing on the issue of the iTunes tax.

Ruffini wrote this column, moreover, in the same week when the big three U.S. automakers announced that they were shutting down production due to imminent bankruptcy -- an economic issue that is far more important in the lives of Americans than whatever additional cost they might incur when downloading Paul McCartney's latest album. On the issue of what should be done about the auto industry, however, Ruffini has been resolutely silent.

Let's get real here. How prominently do you think something like "the iTunes tax" will loom in the minds of New Yorkers, let alone the auto industry's factory workers, parts vendors, salespeople and other affected parties, when the next U.S. elections roll around? One thing we saw during the last election is that shallow posturing based on symbolism and minor issues can no longer take the place of real, serious thinking about hard choices during difficult times. If shallow symbolism still did the trick, "Joe the Plumber" would have made John McCain America's next president. Like most ideological conservatives, however, Ruffini is so mired in ideological thinking about "no new taxes" that he really thinks the iTunes tax might be his party's path to victory.

Let's get real here. How prominently do you think something like "the iTunes tax" will loom in the minds of New Yorkers, let alone the auto industry's factory workers, parts vendors, salespeople and other affected parties, when the next U.S. elections roll around? One thing we saw during the last election is that shallow posturing based on symbolism and minor issues can no longer take the place of real, serious thinking about hard choices during difficult times. If shallow symbolism still did the trick, "Joe the Plumber" would have made John McCain America's next president. Like most ideological conservatives, however, Ruffini is so mired in ideological thinking about "no new taxes" that he really thinks the iTunes tax might be his party's path to victory.

Health Matters

Ruffini concludes his piece by asking, "with out-of-control health care costs being a big driver of spending at the state level, will the GOP put forward a compelling agenda on controlling health care costs? The health care debate at the federal level has focused mostly on the question of access -- but the problems people experience most directly are on different axes: cost and quality. With waste accounting for up to half of U.S. health care spending, it is the states -- as the biggest direct consumers of health care -- that have the biggest incentive to do something about it. Will any of them step up and do something radical?"

Here again, he offers nothing by way of actual policy suggestions for ways that health care costs could be constrained. Although he speaks in vague terms about developing a "compelling agenda," he seems primarily interested in symbolism rather than the substance of governing.

Once again, let's get real here. For starters, let's recall some facts and history. Fifteen years ago, conservatives in league with the U.S. healthcare industry successfully beat back the Clinton administration's efforts at health reform through a massive lobbying effort that include the now-infamous "Harry and Louise" advertising campaign. This campaign made two claims: First, it warned that Clinton's plan for government-sponsored health coverage would eliminate needed health services that Americans are used to receiving. Second, it claimed that the Clinton plan would increase health costs to as much as "$3,200 a year" (gasp). (Here's the link to a YouTube video of the ads where they cite that figure.)

As I pointed out recently, this dire-sounding figure of $3,200 a year actually sounds cheap compared to what Americans are paying today. The very outcomes that conservatives warned about in 2003 have come to pass as a consequence of their own policies. People are losing access to health care, and costs have risen astronomically. Once Bush took office and Republicans took control of both houses of congress, these trends accelerated. Republicans and the Bush administration eagerly colluded with the private health industry in ways that guaranteed costs would increase. Their 2003 Medicare bill not only committed the government to $400 billion in new spending, but actually forbade the government from using its bargaining power to negotiate better prices when buying drugs from pharmaceutical companies.

The United States currently spends more money per capita on health care than any other country in the world. It is actually spending more than double the $3,200 per year that "Harry and Louise" fretted about. As the U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) noted in a recent study, "the United States spent $6,102 per capita on health care in 2004 -- more than double the OECD average and 19.9% more than Luxembourg, the second-highest spending country. In 2004, 15.3% of the U.S. economy was devoted to health care, compared with 8.9% in the average OECD country and 11.6% in second-placed Switzerland."

Every year now sees dramatic increases in health care costs. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has projected that the U.S. will spend $7,868 per person on health care for 2008, or 16.6% of our gross domestic product (GDP). Based on present trends, a decade from now we'll be spending $13,101 per person (19.5% of GDP).

Ruffini is certainly correct, therefore, when he points out that cost containment is an important concern for U.S. health policy. However, talk about cost containment needs to be accompanied by some sort of plan to actually achieve it. And despite Ruffini's vague talk about "controlling health care costs," he doesn't even hint at a policy approach that would actually do so. Once again, he limits himself to mouthable slogans rather than actual policies for governance.

As it happens, there are lots of policy models available for anyone who is serious about controlling U.S. health care costs. Given that the United States is currently spending more than any other country, we have a wealth of alternatives to choose from. For starters, let's take a serious look at what Japan is doing, since the Japanese live longer than everyone else and pay just about a third of what we pay for health care. Or, if you prefer, let's study the examples of Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, or the United Kingdom. In each one of these countries, people not only spend substantially less on health care than in the United States, but they have a longer life expectancy.

In short, there's no shortage of policy options care reform. All we have to do find an example that works and develop a plan to implement it.

But wait -- there's a problem. In every one of the countries I just listed, health care is primarily funded by the government, and the idea of following this example runs contrary to the central dogma of conservative ideology, which holds that government social programs are always wasteful and bad. For every problem, therefore, conservatives believe that the solution is privatization and eliminating down government spending. This assumption would imply that the country whose health system is most privatized (the United States) should be expected to have the most cost-effective system. But let's look at some data:

| Government Health Care Spending in 2004 as a Percentage of Total Health Care Spending |

|

| Australia | 67.5% |

| Austria | 76.5% |

| Canada | 70.2% |

| Germany | 77.0% |

| Japan | 82.7% |

| Norway | 83.5% |

| Spain | 70.6% |

| Sweden | 81.7% |

| United Kingdom | 86.9% |

| United States | 45.1% |

| Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development | |

With regard to containing health costs, reality is producing the exact opposite result of what conservative doctrine predicts. Faced with this evidence, the practical, sensible thing to do would be to adjust your doctrine and act accordingly. I hope someone will call and let me know when the conservative movement actually makes this adjustment.

I really wish they would, and I'm not speaking facetiously. Throughout its history, the United States has governed with the effective participation of two political parties. A system dominated by a single political party is in danger of ideological excess and arrogance, something we saw in abundance during the Bush years (a phenomenon that John Stauber and I discussed in our 2004 book, Banana Republicans). I don't think there is anything inherent in the personalities of Barack Obama or the Democratic Party leadership that will prevent them from succumbing to similar tendencies. To govern well, they actually need to be challenged by a rival party with opposing ideas.

To play this role, however, the challenger needs to be grounded in reality. The sad thing about the conservative movement is that it has become so indoctrinated in its own propaganda that it has lost touch with reality.

It wasn't always this way. I remember a time when conservatives seriously thought about balancing budgets when they talked about economic policy. There was some sense to that. After eight years of record budget deficits under Bush, however, they've gotten so used to ignoring the relationship between income and expenses that they're reduced to silly posturing about things like the iTunes tax.

There was a time, moreover, when conservatives believed that taxation and government spending could serve positive purposes. It was President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a conservative, who refused to push tax rate cuts for high-income Americans. He took that position at a time when the top tax rate on income over $400,000 stood at 91 percent. Our current top marginal rate is 35 percent. Remember during the recent election when John the McCain joined Joe the Plumber in calling Obama a socialist for saying the top marginal tax rate should be raised to just 38 percent? Where were the conservative voices then who remembed that good old Ike once supported a marginal tax rate that was more than double what they now call "socialism"?

The Eisenhower tax rate financed not only the G.I. Bill, which today's conservatives would deride as a "government entitlement," but also underwrote the construction of the U.S. Interstate Highway System, the largest public works project in history. The highway system, of course, also helped keep the auto industry viable for all these years. Something like that today would be unthinkable under current conservative doctrine, which pretends that government spending does nothing but drain away wealth from the private sector, a pretense which can only be sustained by pretending that that things like highways build themselves. (The fact that government spending supports and often subsidizes the private sector is something that should have been obvious even before the recent government bailouts of Wall Street and Detroit.)

It's more or less the same story with our collapsing health care system. The absence of a publicly-funded health system might mean lower taxes in theory, but in practice it has not made the private sector more profitable (with the exception of private health providers, who obviously profit greatly from the current arrangement). In practice, the lack of a public health system actually dumps higher costs on the private sector. The failure to achieve health care reform in the United States is therefore contributing to the financial woes not only of states like New York but also of economic sectors like the automobile industry, which find themselves increasingly burdened by the expectation that they finance health insurance for their workers.

These are some of the realities that conservatives like Patrick Ruffini are going to have to face if they really want to reinvent and revitalize their movement. Of course, it's never easy to give up cherished dogma. If they want a place at the decision-making table in the 21st century, however, they'll need to stop repeating ideological mantras and actually try thinking for a change.

Comments

Anonymous replied on Permalink

iTunes taxes and a second party...