Submitted by Lisa Graves on

Scholars at UC Berkeley recently released a study finding that low wages in the fast food industry cost taxpayers $7 billion every year in a raft of social supports that subsidize the salaries of these low-income workers. The professors argue that the minimum wage should be increased to relieve the burden on taxpayers who underwrite super-sized restaurant industry profits.

But as the bona fide academic study rolled out, multiple media outlets ran comments criticizing the report's numbers and methodology from the scholarly sounding "Employment Policies Institute (EPI)." The Austin Business Journal characterized EPI as a think tank "which studies employment growth," while the Miami Herald ran a quote from Michael Saltsman, who the paper named as EPI's "research director."

But as the bona fide academic study rolled out, multiple media outlets ran comments criticizing the report's numbers and methodology from the scholarly sounding "Employment Policies Institute (EPI)." The Austin Business Journal characterized EPI as a think tank "which studies employment growth," while the Miami Herald ran a quote from Michael Saltsman, who the paper named as EPI's "research director."

For his part, Mr. Saltsman ran aggressive op-eds against any minimum wage increase in papers such as the The Missoulian, where he was described as EPI's "research fellow." In an op-ed he wrote for the Washington Post, his title was listed as EPI's "research director" but with a notation that EPI "receives funding from restaurants, among other sources." But even this partial disclosure provides a disservice to readers in the nation's capital.

In fact, the Employment Policies Institute operates from the same office suite as Berman and Company, a public relations firm owned by Richard Berman. This is not an opinion; it's a fact anyone can verify by viewing EPI and Berman and Company's websites. The 990 for the Employment Policies Institute Foundation (EPIF) lists Rick Berman as the CEO; in 2011 his for-profit firm was paid $1.5 million of EPIF's total $2.1 million budget. If you're wondering how a PR company could so easily fool newspapers across the country -- including the Post, which regularly pats itself on the back for breaking Watergate -- then you haven't woken up to the crisis of American journalism.

According to Pew Research Center, newspaper newsrooms have shrunk 30% since 2000, leaving fewer than 40,000 newspaper employees across the country, the lowest number since 1978. In such a depressed media environment -- where there are four public relations flacks for every reporter, compared to a 1-to-1 ratio in the 1960s -- it is not surprising that a P.R. company could successfully rebrand itself as a think tank and capitalize on an acronym held by an actual think tank, the Economic Policy Institute, with 20 staff and 36 respected research associates. Unlike the Berman group, the Economic Policy Institute lists its staff, its raft of experts, its board, its annual report and its annual audit, which shows its funders, right on its website.

At the Center for Media and Democracy, we have spent twenty years tracking disinformation and spin, and Richard Berman has long been one of our favorite research subjects. Berman came out of the restaurant industry, spending several years as a top executive at Steak and Ale before launching Berman and Company to help advocate for corporate America. His clients have included tobacco companies (for which he formed an entity he called the Center for Consumer Freedom) and the alcohol industry (for which he created the American Beverage Institute). He was once profiled on a 60 Minutes piece titled "Dr. Evil." But one of his most successful products has been the Employment Policies Institute.

EPI regularly opines in the press on a host of topics. Recently EPI has been working to show that restaurant workers don't need higher wages or paid sick days, but few Americans are informed by the press that this "think tank" is just one or two working for spinmeister Berman, likely on a contract for the restaurant industry.

We recently analyzed three years of newspaper stories from across the country that quoted from EPI or Michael Saltsman.

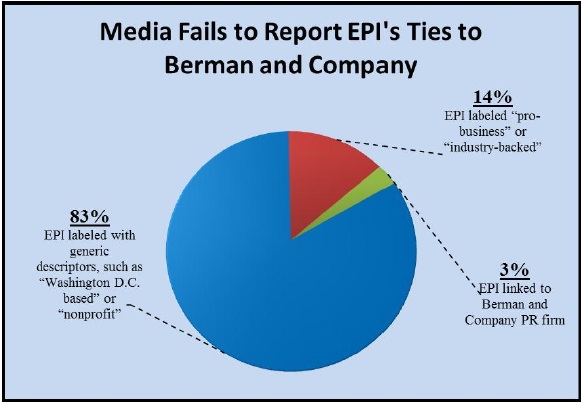

In 83% of the stories we examined, reporters provided readers with no information about EPI's relationship with Berman and Company. In most cases, journalists stated that EPI is a "Washington DC nonprofit" and called Saltsman a "research director." In some instances, reporters took tentative steps in the right direction and called EPI "conservative" or "pro business." Only about 3% of the time did they correctly link EPI to Berman and Company.

Failing to note EPI's role as an arm of Berman and Company fools readers into thinking they are a legitimate and independent voice in national politics. In 37% of stories we found reporters tapped EPI to counter positions by government experts or politicians; in 39% EPI was used to counter policy experts at nonprofits; and 22% of the time, EPI was used as a counterpoint to academics at American universities.

Certainly corporations have a right to have their voice heard, but that voice should be their own; not that of phony experts on retainer.

This article originally appeared in Salon.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 1.67 MB |

Comments

Douglas Naphas replied on Permalink

The first link is to the wrong address

Peter B replied on Permalink

Five days after you pointed this out...